My most recent hike covered the most important of Taiwan’s historic cross-island trails: the week-long Batongguan, which crosses the alpine spine of Yushan National Park.

As this is such a great trail, and one for which there is so little English information, this is going to be a very long blog entry. For ease of navigation, I will divide it into 8 parts, the first of which will center on the history of the trail and overall practicalities:

History of the Batongguan Trail:

My journey into Taiwan’s rugged highlands was made possible by a little know incident way back in the spring of 1874. Paiwan aboriginals had murdered a crew of Japanese sailors and attempts by the Meiji government to force the Qing to punish tribal leaders led to the flimsiest of excuses: we don’t have any control over this part of Taiwan. Sorry.

Angered (or looking for a good excuse to scout out the island), the Japanese government sent a punitive expedition of 3,600 soldiers. Under the leadership of one Saigō Tsugumichi (which sounds uncomfortably close to tsutsugamuchi, the disease I was struck with in January) forces invaded southern Taiwan in May 1874. As with a similar assault by US marines in 1867 against aboriginals and pirates in Kenting, the battle was not exactly favorable to the invaders. The Paiwan suffered loses of about 30 men. The Japanese, 543 (12 killed in battle and 531 by disease).

In Taiwan, the expedition is known as the Mudan Incident and there is a monument on one of the battlefields in a large field off Hwy 199 in Pingtung County. It’s not far east of the popular Sichongshi Hot Springs.

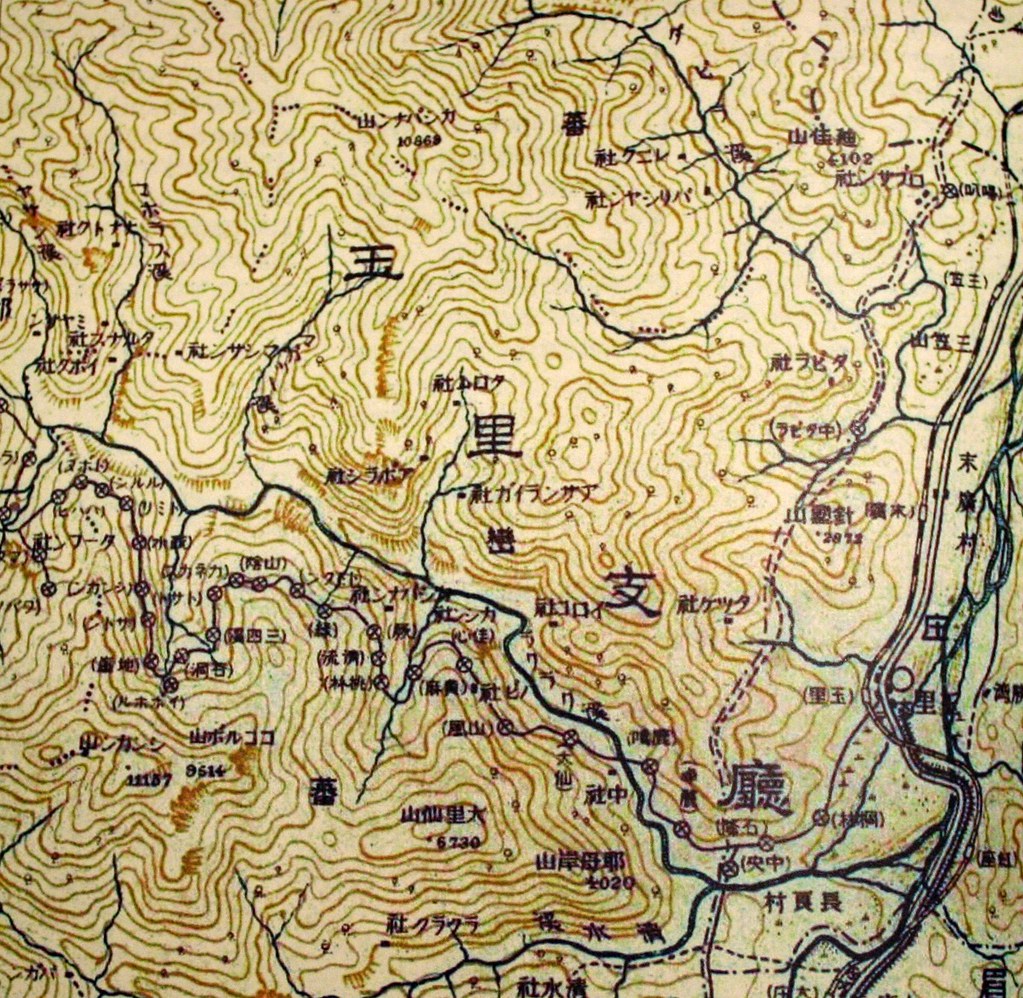

The Qing were understandably not happy to be shown to have little control of their territory and so in 1875 sent ambassador Pao-chen Shen to oversee the strengthening of Taiwan's defenses. Shen took charge of developing and charting the mountains, and placating (subjugating) the aboriginal tribes. The project for engineering the Batonguan trail began that same year.

The project was headed by an officer named Wu Guang Liang, who commanded 2000 soldiers from the Flying Tiger Corps. Wu’s route started off at Chushan, Nantou County, passed through Lugu and Hsinyi Villages, climbed over the Batongguan meadows and the Hsiuguluan Mountains, and ended finally in Yuli in Hualian County. In total the route was 152km long.

Today, the trail remains intact (but in poor shape) only after Dongpu though in several towns such as Jiji and Lugu there are commemorative stele. This one has an inscription by Wu Guang Liang himself.

The path took a year to complete and was called the Batong Pass Route, though there is no actual mountain pass to cross. Wu decided to use the name Batongguan (which is a transliteration of the Bunun “Pan Toun Kua,” their word for Yushan) as it sounded like the Chinese for “being able to pass unhindered.” Or maybe not. We have read of competing versions of the name.

In any case, that is the Qing Dynasty Batongguan Trail. But there is also the Japanese Era Batongguan Traversing Route, which is what we hiked. Both trails both have a common point at Dongpu. They join up again at Batongguan (some reports suggest that the trails are the same from Dongpu to Batongguan) and for the last time at Dashuiku. In general the Qing Dynasty trail follows a harder, higher, more northern route.

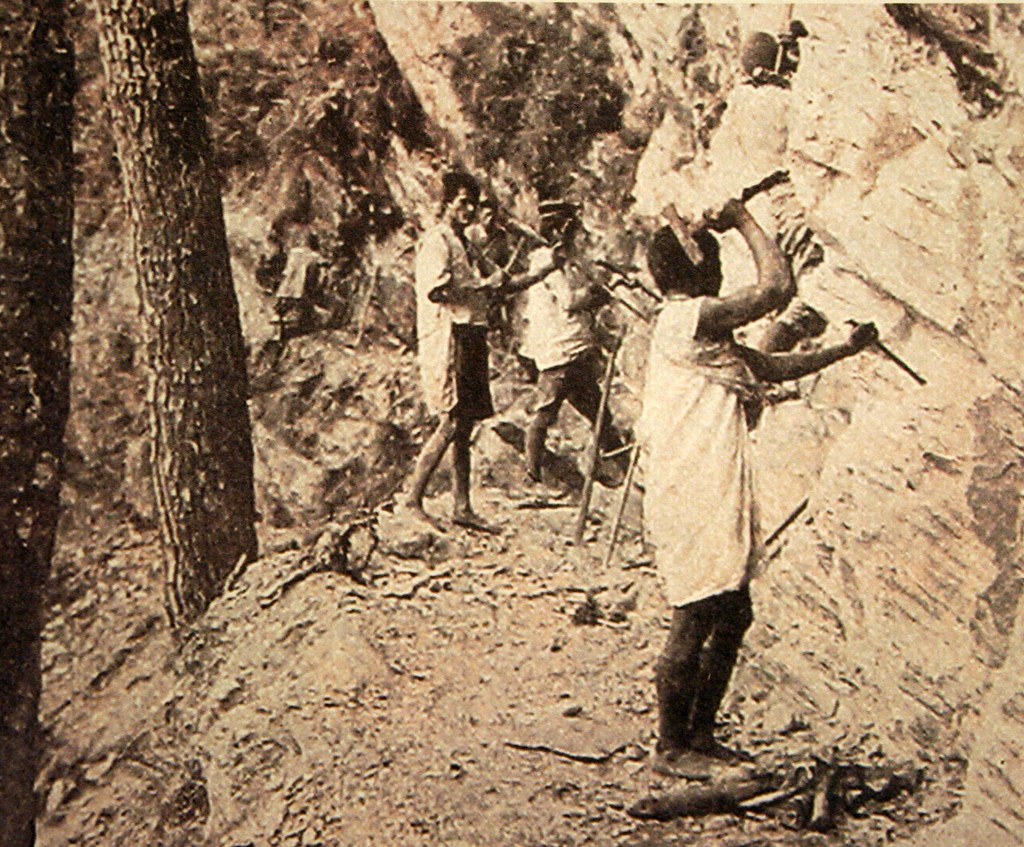

The Japanese route was in part designed to facilitate transportation and communication between eastern and western Taiwan. But to a large degree it was built to pacify the aboriginals in the highland areas (using their labor of course).

Surveying for the trail began in 1919, with the entire stretch being completed by 1921. However, it does seem that parts were already in place. By 1910, according to reports I have read, there was a trail from Yuli to at least Dafen. Dafen (also Tahun) was a major outpost with a school, martial arts and ceremonial hall, munitions depo, and trading post.

Dafen became the center of the colonial government’s attempts to control the Bunun around the Laku Laku River Valley. An inflexible policy banning all aboriginal firearm possession was met with such resistance (the Bunun revered guns) that police stations had to be set up every 2-4km along this part of the trail. To this day, commemorative steles marking bloody battles can be spotted every few kilometres.

Click here to see Day One.

Practicalities:

The Japanese Era Batongguan Traversing Route is about 90km long. While it has suffered numerous landslides and washouts over the years, in addition to the unforgiving shifting of tectonic plates, repairs that began in the last 1990s have restored it to a perfectly hike-able condition for most anyone in good shape. There are markings every kilometer or so, and maps and interpretative signs in strategic places. There is also an excellent system of free cabins and campgrounds.

A tent is still recommended however, as there is a 12 hour stretch between the Dashuiku and Dafen cabins, which not everyone may want to do in a day. The weather could also force you into making a shorter day of it. In any case, there are numerous campgrounds along the trail. As these used to be former police stations the ground is flat and sheltered.

One needs permits from Yushan National Park to hike the trail. These permits usually book you into cabins for the first couple nights. After that, it’s first come first serve, though the trail is hardly busy. We didn’t encounter anyone else on the trails for 3 out of 6 days.

Water sources are plentiful, both at the cabins and from side streams. I mention the availability of water in each day’s entry.

The cabins do not have blankets but they do have thick mattresses, solar powered lighting, and in some cases, toilets. The Dafen cabin has solar heated showers, which are heaven sent after 5 days on the trail.

Most people take seven days to complete the trail. We did it in six. Eight would be ideal as it would allow time to climb some of the higher peaks, as well as spend time in the alpine meadows with the sambar deer.